The Impact of the Mona Lisa

Hussain Ibn AhmedBy Mohamed Ismail Abdalla – Visual Artist, Alexandria, Egypt – July 2022

Instagram: @m_ismail_abdalla

Spending time in front of a single piece of art offers the viewer an opportunity to form a deep connection with the painting or sculpture. This bond gradually grows on both intellectual and emotional levels; sincere contemplation opens a gateway to emotional resonance, exploration, discovery, knowledge, and enlightenment. The viewer might find themselves fascinated by a work they previously overlooked. This act of reflection may even drive them to explore broader horizons of interpretation and delve into the visible and hidden layers of the artwork.

Along this path, some artists and fine arts students are drawn to recreate classical artworks as a means of gaining knowledge, honing technical skills, and uncovering the secrets of light and shadow expressed through the flowing color gradations on faces and the luminous landscapes of legendary classical painters.

Sometimes, recreating a classical painting stems from personal motives—artistic adventure, analytical study, or pure pleasure. Perhaps one of these thoughts occupied artist Louis Béroud’s mind on August 22, 1911, when he headed to the Louvre to create a preparatory sketch of the Mona Lisa. He was struck by disappointment when he found the wall where the painting had hung completely bare. His insistence on knowing what happened led to the shocking discovery of the Mona Lisa’s theft.

The French authorities responded swiftly. The museum was closed, all staff were interrogated, and the borders were sealed in fear of the painting being smuggled out. Even Pablo Picasso and his poet friend Guillaume Apollinaire were questioned based on a tip from Apollinaire’s former secretary.

At the time, Picasso was a promising 30-year-old artist who had already completed his groundbreaking work Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which paved the way for Cubism. Yet despite his rising stature, he and Apollinaire were still summoned and eventually cleared of any suspicion.

Pablo Picasso

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

There’s no doubt that by then, the Mona Lisa had already earned a degree of fame within artistic circles. But the 1911 theft marked a turning point in its history, catapulting it into global renown. A media frenzy erupted, with newspapers racing to identify the thief and uncover the details, placing the Mona Lisa in the spotlight of public attention. Crowds of visitors—including Franz Kafka—flocked to the Louvre after it reopened, leaving bouquets of flowers beneath the vacant wall where the Mona Lisa had once hung.

The search lasted for two fruitless years until Vincenzo Peruggia was arrested in Florence after attempting to sell the painting. During his trial, he claimed that he stole it out of patriotic duty—to return Italian artworks stolen by the French during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). What he didn’t realize was that the Mona Lisa had entered France legally, brought by Leonardo da Vinci himself.

Ironically, Peruggia’s act unintentionally made the Mona Lisa the most famous painting in the world. Yet it’s clear from his statements that he had little understanding of the painting’s historical and artistic value. His choice of the Mona Lisa seemed arbitrary—it was simply the smallest of the Italian paintings on display, making it easier to conceal under his coat and escape unnoticed.

Vincenzo Peruggia

Still, it would be unfair to attribute the Mona Lisa’s legendary status solely to Peruggia’s crime. The painting’s value in art history cannot be reduced to an incident of theft.

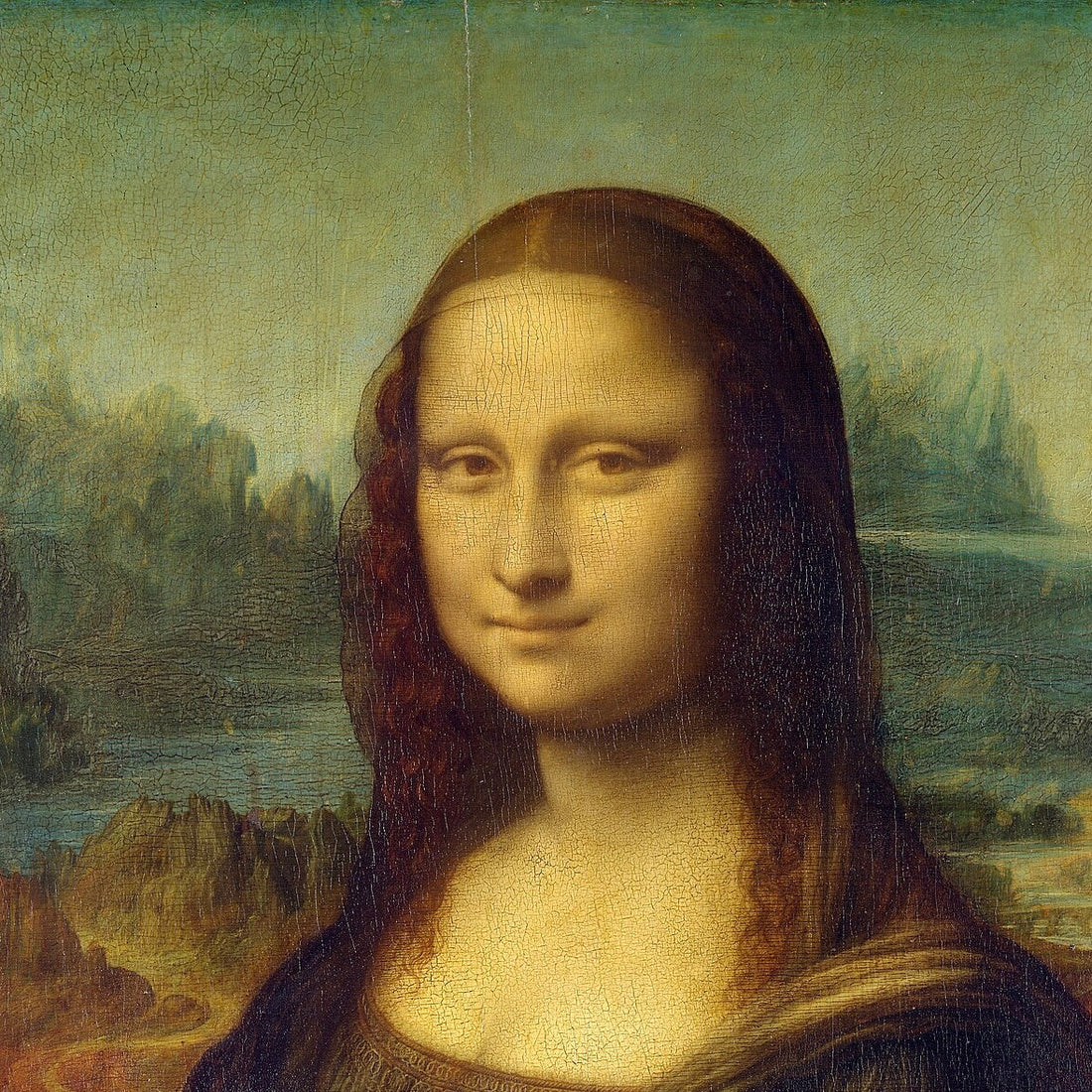

To the modern viewer, the Mona Lisa may appear rather simple, perhaps lacking the flair and drama found in many other celebrated artworks. Yet by Renaissance standards, it was a groundbreaking masterpiece of unmatched skill and genius. It had a profound impact on Leonardo’s contemporaries, becoming a model in portrait painting.

In later eras, the Mona Lisa was imbued with mystery and allure, sparking countless theories, myths, and speculations. Her serene face, bathed in shadow and light, gazing at us with a puzzling expression, continues to invite interpretation. Despite the ongoing debate over her true identity, most paths lead back to Lisa Gherardini.

Leonardo began painting Lisa Gherardini in 1503, commissioned by her husband Francesco del Giocondo, a wealthy silk merchant from Florence. And here begins the first puzzle. At that time, Leonardo was 51 years old, highly acclaimed, and received commissions from nobility. Why would a master of his stature take on a modest commission like this—especially after painting The Virgin of the Rocks and The Last Supper?

The most logical explanation, according to researchers, is that Francesco had connections to Leonardo’s father, Piero da Vinci, who likely mediated the commission. It also came soon after Leonardo had returned to Florence from Milan—suggesting he may have needed income at the time. Still, there seems to be a hidden reason that moved Leonardo—one we may never truly uncover.

Leonardo patiently applied his masterful technique to the wooden panel using sfumato, a method he pioneered. This involved blending translucent layers of paint to create seamless gradations of light and shadow, eliminating any visible brushstrokes. The result was a face rendered with astonishing realism.

Leonardo also introduced something new to portraiture—the sense of the subject being aware of the viewer. Prior to this, women in portraits appeared unaware of being observed. They lacked the self-assured gaze typically reserved for male figures of the era. But Mona Lisa breaks this pattern. She knows we’re watching. She meets our gaze with subtle confidence, asserting an awareness of self that was rare for women in Renaissance art.

The Mona Lisa

Portraits of the era often depicted figures with stern, proud expressions, draped in luxurious garments and jewelry to display wealth and social status. The Mona Lisa wears a plain dark dress, devoid of adornment, despite being the wife of a wealthy merchant. This visual contrast invites us to focus on what she does possess—her captivating smile.

Perhaps Lisa Gherardini truly had a smile that enchanted Leonardo, one that lingered in his dreams and haunted his imagination, reappearing in many of his later works. That smile, dubbed the “Leonardesque smile,” was revolutionary. To craft it, Leonardo drew upon his deep understanding of anatomy, keen observation, and unmatched artistic skill. He poured his passion into it, giving us a smile that continues to stir emotions—confusing, enchanting, and deeply moving.

Taking into account the Mona Lisa’s uniqueness and enduring influence over five centuries, we come to a vital truth: Leonardo da Vinci created a pioneering, radical work for his time—setting a standard for portrait art followed by generations of painters. This, in my view, is what truly cements her place in the world of art, far beyond myths and controversies.

There are no definitive records on how long Leonardo spent painting the Mona Lisa. Some believe it took four years; others disagree. What we do know is that he never delivered the portrait to Francesco and Lisa. He kept it with him, even bringing it to France when invited by King Francis I. After Leonardo’s death in 1519, the king acquired the painting, as prearranged. From there, it traveled from the Château de Fontainebleau to Versailles, and after the French Revolution (1789–1799), it found its home in the Louvre.

Great works of art are inherently mysterious. They hold deep, often hidden meanings, revealing themselves slowly—if ever—through insight and emotion. They don’t offer easy answers but invite us to project our thoughts and feelings upon them, giving them new life within each viewer. The Mona Lisa has done just that—stirring love, admiration, curiosity, and satire.

Artists such as Raphael, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, and Fernando Botero have reinterpreted her. She has also sparked hatred and vandalism: stoned in 1956, painted over in 1974, doused with coffee in 2009. Most recently, on May 29, 2022, a man disguised as an elderly woman in a wheelchair threw cake at the painting. The protective glass was smeared with cream—yet from behind the glass, the Mona Lisa smiled on, serene, radiant as ever, meeting our gaze.

Images notes:

- Title image: Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci, from C2RMF retouched.

- Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907, oil on canvas, 244 x 234 cm; arguably the first cubist painting.

- Picasso in front of his painting The Aficionado (Kunstmuseum Basel) at Villa les Clochettes, summer 1912.

- Mug shot of Vincenzo Peruggia, who was believed to have stolen the Mona Lisa in 1911